Background: Henrietta Marie was a British slave ship that sank in 1700. Part of the Triangle Trade, the ship made its way from England to Africa in December 1699.

After loading the ship with enslaved Africans and other cargo, it made the journey to Jamaica, arriving in May 1700.[1] While enroute back to London after delivering enslaved Africans to Jamaica, the ship was hit by a hurricane and sank. Henrietta Marie was located 35 miles off the coast of present-day Key West, Florida.[2] There were no slaves aboard when the ship sank.

Interdisciplinary Involvement

Henrietta Marie was first discovered in 1972 by Captain Demostenes “Moe” Molinar, a boat captain from Panama and well-known underwater treasure hunter who was hired by Mel Fisher, a commercial salvor and treasure hunter. He was interested in finding the Spanish treasure galleon Nuestra Senora de Atocha. Abandoned after its initial finding, Henrietta Marie remained largely unexplored for over a decade until 1983.

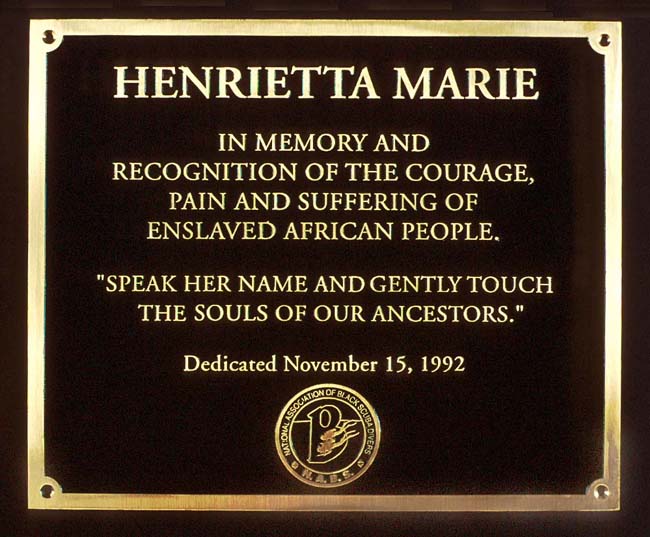

Archaeologist David Moore was studying the slave trade and heard about this ship, believing it was associated with the Transatlantic Slave Trade. In 1983, salvor Henry Taylor and David Moore, along with a team of divers, were hired to work on the wreck. In 1988, the Mel Fisher Maritime Heritage Society (MFMHS) began overseeing the wreck. Dr. Corey Malcom, lead historian at the Florida Keys History Center and former Director of Archaeology with the Mel Fisher Museum continued documentation of the site in 1991 and 2001.[1] In 1993, a bronze memorial plaque facing toward Africa was placed at the site by the National Association of Black SCUBA Divers (NABS).[2] In 2005, NABS sponsored dives for ten young inner-city African American students from Nashville, Tennessee to visit the Henrietta Marie site. This program evolved into a partnership with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and came to be known as Voyage to Discovery, “an initiative to discover the untold stories and maritime achievements of people of color through education, archaeology, science, and underwater exploration.”[3]

[1] Jane Webster, “Slave Ships and Maritime Archaeology: An Overview.”

[2] “The Henrietta Marie an English Merchant Slave Ship, Wrecked 1700,” Mel Fisher Maritime Museum.

[3] Michael H. Cottman, Shackles from The Deep: Tracing the Path of a Sunken Slave Ship, a Bitter Past, and a Rich Legacy (Washington, D.C: National Geographic, 2017), 117.

Museology

In 1993, Mel Fisher donated his claim to Henrietta Marie’s wreck site and the retrieved artifacts to the Mel Fisher Maritime Heritage Society. The MFMHS continues to fund research and conservation for this wreck site.

In 1995, the MFMHS opened “A Slave Ship Speaks: The Wreck of the Henrietta Marie,” the first major museum exhibition in the United States dedicated to a ship involved in the Transatlantic Slave Trade. This exhibition was prepared with support from leading African American historians and traveled the United States and the Caribbean for close to 20 years.[5]

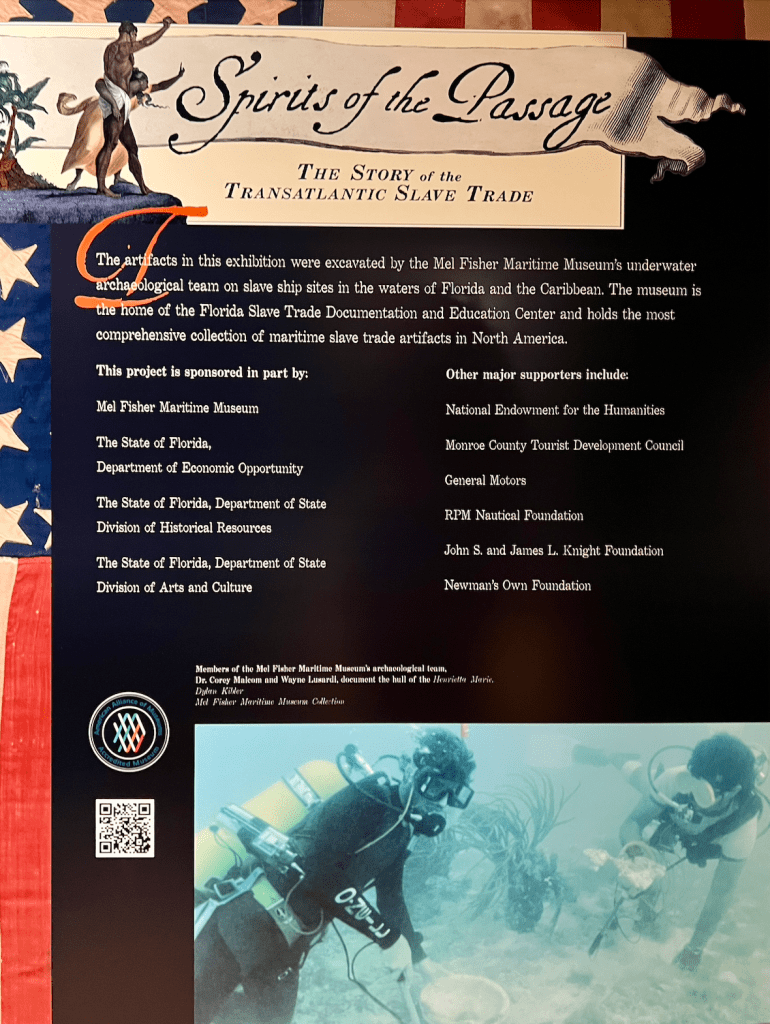

In late 2024, the Mel Fisher Maritime Museum revealed a new, permanent exhibit, “Spirits of the Passage: The Story of the Transatlantic Slave Trade,” which documents the slave trade and Key West’s role in it using a collection of artifacts, models, audio recordings, graphics, and interactive displays.[6] This exhibit not only does the important job of educating visitors on the slave trade, the interactive approach brings life to those aboard the ships, humanizes the enslaved, and cements their role in our collective memory and consciousness.

Image: Author’s own from MFMHS exhibit

Material Culture

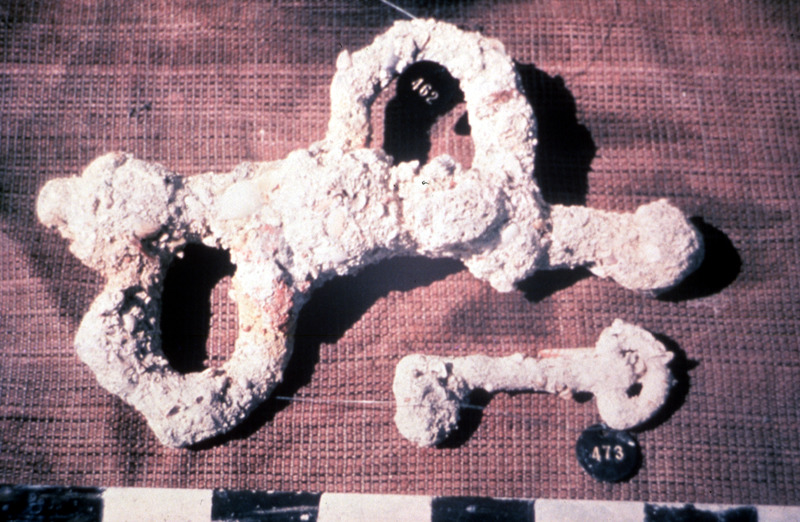

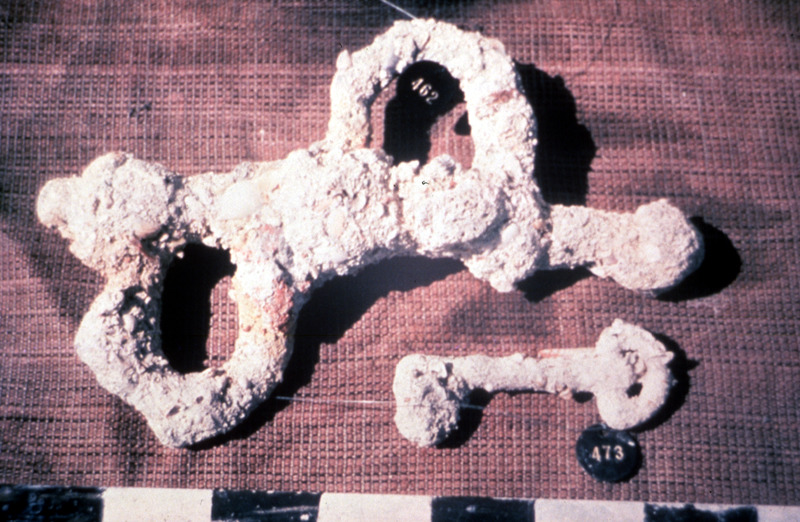

Many shackles were first discovered in 1972, including children’s sized shackles and an 800-pound iron cannon. In 1983, the ship’s bell was found, making it possible to confirm the ship’s identity, and the year she was built, in 1699. Knowing the ship’s name, historians used shipping and trading records from Jamaica and England to piece together the ship’s story. Because the ship had been underwater for nearly 300 years when it was discovered, the wood where the ship’s name may have appeared was disintegrated. If the bell had not been found, the ship’s identity would likely have remained a mystery.

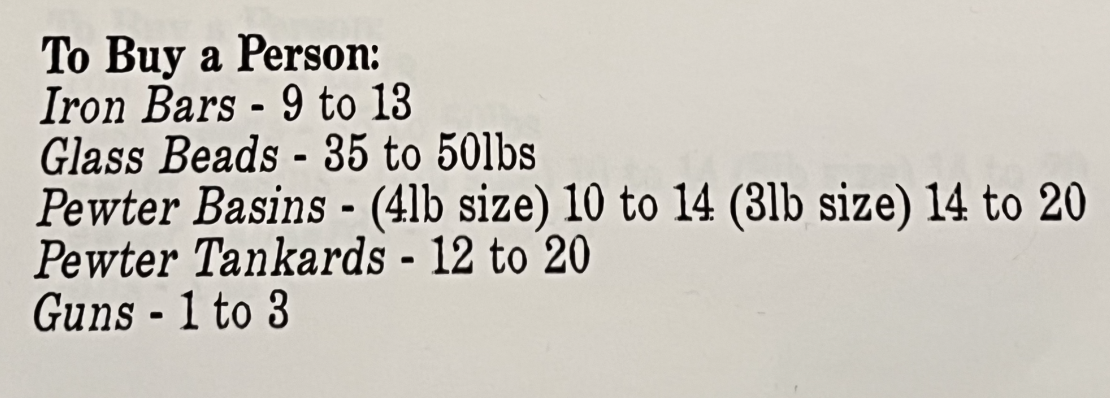

Glass Beads and the Value of Human Lives

Objects found at the shipwreck site include over eighty sets of shackles, two cast-iron cannons, thousands of colorful glass beads cheaply made in Italy that came to be traded for African lives[3], “stock iron trade bars, ivory “elephant’s teeth,” and a large collection of English made pewter tankards, basins, spoons and bottles. The partial remains of the ship’s hull have allowed for an understanding of the ship itself.” [4]

Objects found at the shipwreck site include over eighty sets of shackles, two cast-iron cannons, thousands of colorful glass beads cheaply made in Italy that came to be traded for African lives[3], “stock iron trade bars, ivory “elephant’s teeth,” and a large collection of English made pewter tankards, basins, spoons and bottles. The partial remains of the ship’s hull have allowed for an understanding of the ship itself.” [4]

35 to 50 pounds of these glass beads would have been the equivalent of one life.

Images: Author’s own from MFMHS exhibit

Door of No Return

Images: Author’s own from MFMHS exhibit

Prior to being forced aboard a slave ship, many kidnapped Africans found themselves imprisoned below Cape Coast Castle in Ghana while they awaited their fate. When ships were ready for their human cargo, Africans would be forced toward the beach through the Door of No Return. The temporary blindness caused by moving from the castle’s dungeon into bright sunlight made it easier for those waiting on the beach to grab their prisoners, get them into boats, and row them out to the waiting slave ships.[1] For most Africans, the Door of No Return would represent their last time on African soil.

Toward the end of the “Spirits of the Passage” exhibit, a dark and narrow hallway waits for visitors, a symbolic Door of No Return. After reading about the Door of No Return, I moved into the dark passage, meant to simulate a ship’s slave hold, where all my senses were engaged. Below my feet, wooden planks made it feel as if I was aboard the ship and sounds of ocean waves, shouts of the crew, and the clinking of shackles could be heard in the distance through unseen speakers. To my left, shackles of all sizes excavated from the Henrietta Marie were on display, the variety in sizes serving as a physical reminder that even small children were victims of the slave trade. Who made these child-sized shackles, and how were they able to sleep at night knowing what they would be used for? To my right, half decks were crowded with Plexiglas figures of chained Africans. In combination with the narrow passageway, this visual experience evokes discomfort and confinement, a momentary glimpse into the inhumane conditions Africans faced aboard the Henrietta Marie and other slave ships.

[1] “Spirits of the Passage: The Story of the Transatlantic Slave Trade” (Key West, FL: Mel Fisher Maritime Museum, 1995).

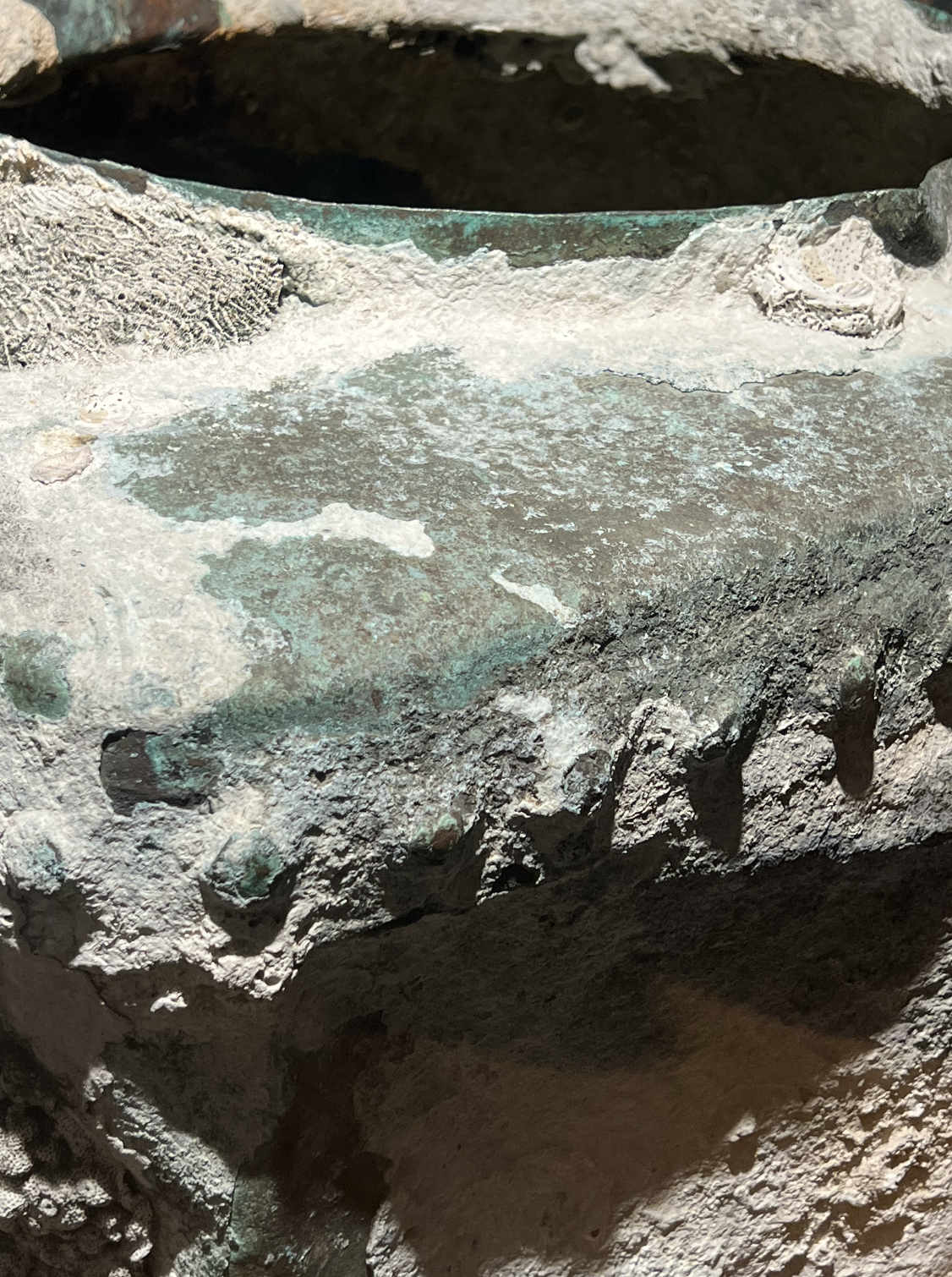

Copper Cooking Cauldron

I’ve seen photographs and written about the large cooking cauldrons that were used to feed slaves aboard and that discovering one of these large cauldrons at a wreck site was a likely sign that the ship carried slaves at some point. By comparing two types of cauldrons found at the Henrietta Marie site, Dr. Corey Malcom, Director of Archaeology at the Mel Fisher Maritime Museum demonstrates the dietary inequality present on board between crew and Africans. A smaller, two-chambered cauldron recovered would have been used to prepare two-course meals for the small crew. Slaves on the other hand, numbering over 200, were fed from one giant, single-chambered pot, reflecting the monotonous meals Africans were forced to eat on board.[1] Common meals consisted of beans, yams, or rice, and meals were calculated to cheaply meet minimum basic nutrition requirements, to keep the enslaved alive until they could be sold.

I wasn’t prepared for the size of the cauldron; designed to hold 85 gallons, my 5’4” frame easily could have fit inside. Contemplating the cauldron in person quickly put into perspective the sheer number of enslaved Africans who were typically crammed on board a slave ship. I pictured the food prepared here and wondered how many hands touched this cauldron. African names and identities were rarely recorded during the slave trade, but tangible artifacts remain as evidence of the horrors of the slave trade.

[1] Corey Malcom, “The Navigator: Newsletter of The Mel Fisher Maritime Heritage Society,” February 2000.

Listen to the sound of Henrietta Marie‘s bell below.

The bell would have been rung every half an hour to mark time aboard the ship. Video and recording from the Mel Fisher Maritime Museum.

Historical Significance

To date, the Henrietta Marie is the oldest sunken slave ship ever excavated in the United States and is believed to be “the world’s largest source of tangible objects representing the early years of the African slave trade, including the largest collection of slave-ship shackles ever found on one site-enough shackles to restrain as many as 325 African people on a single ship.” [7]

While searching for a sunken treasure ship he was hired to help locate, Moe Molinar instead found the Henrietta Marie. After sitting untouched for nearly 300 years, Moe, a black diver and treasure hunter, was the first person to discover the ship, the first person to dive the wreck, and was the first person to touch the shackles that were once used to bind enslaved Africans. [8]

Left: Moe Molinar, photo shared by James Michon

Timeline of Henrietta Marie

1699

British slave ship Henrietta Marie, part of the Triangle Trade, made its way from England to Africa in December 1699

1700

Henrietta Marie Sinks

Enroute back to London after delivering enslaved Africans to Jamaica, the ship was hit by a hurricane. There were no slaves aboard when the ship sank.

1972

Henrietta Marie discovered by Captain Demostenes “Moe” Molinar

Many shackles were first discovered in 1972, including children’s sized shackles and an 800-pound iron cannon

Abandoned after its initial finding, the ship remained largely unexplored for 11 years

David Moore, Site Report: Historical and Archaeological Investigation of the Shipwreck Henrietta Marie

1983

Henrietta Marie‘s bell was found, making it possible to confirm the ship’s identity, and the year she was built, in 1699

1993

A bronze memorial plaque facing toward Africa was placed at the Henrietta Marie site by the National Association of Black SCUBA Divers (NABS).

Michael Cottman gently touches the underwater memorial, which honors the African lives lost during the passages of the Henrietta Marie. Photograph by Courtney Platt/National Geographic Creative

1993

Mel Fisher donated his claim to Henrietta Marie’s wreck site and the retrieved artifacts to the Mel Fisher Maritime Heritage Society (MFMHS)

The MFMHS continues to fund research and conservation for this wreck site

1995

MFMHS opened “A Slave Ship Speaks: The Wreck of the Henrietta Marie,” the first major museum exhibition in the United States dedicated to a ship involved in the Transatlantic Slave Trade

1. “The Wreck of the Henrietta Marie,” West Virginia Department of Arts, Culture & History, 2000, https://archive.wvculture.org/museum/Marie/henrietta.pdf.

2. “The Henrietta Marie an English Merchant Slave Ship, Wrecked 1700,” Mel Fisher Maritime Museum, accessed November 13, 2024, https://www.melfisher.org/henrietta-marie-1700.

3. Michael H. Cottman, Shackles from The Deep: Tracing the Path of a Sunken Slave Ship, a Bitter Past, and a Rich Legacy (Washington, D.C: National Geographic, 2017), 42.

4. “The Henrietta Marie an English Merchant Slave Ship, Wrecked 1700,” Mel Fisher Maritime Museum.

5. “The Henrietta Marie an English Merchant Slave Ship, Wrecked 1700,” Mel Fisher Maritime Museum.

6. Mandy Miles, “Key West’s Mel Fisher Maritime Museum Installs New Permanent Exhibit,” Florida Keys Weekly Newspapers, February 10, 2025, https://keysweekly.com/42/key-wests-mel-fisher-maritime-museum-installs-new-permanent-exhibit/.

7. Michael H. Cottman, Shackles from The Deep: Tracing the Path of a Sunken Slave Ship, a Bitter Past, and a Rich Legacy (Washington, D.C: National Geographic, 2017), 41.

8. Michael H. Cottman, Shackles from The Deep: Tracing the Path of a Sunken Slave Ship, a Bitter Past, and a Rich Legacy, 26.